Studying textiles restores Herstory and helps us understand who we are and how we interpret the world.

Textiles as High Art

Women were great artists lost to HIStory.

Art

Women are depicted frequently in art working with textiles. For many centuries the textile arts were held in as high esteem as painting and sculpture.

Textiles in Myth and History

What was Penelope really doing?

Myth and History

Western history written by men has excluded much of women's history. Written versions of mythology either exclude female mythological personalities or minimize their roles. But, we can discern fragments of powerful goddesses, women warriors, and women explorers who also wove futures, spun threads, and clothed loved ones.

Textiles and Language

"Threads" of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA)

Language

Our everyday speech is replete with metaphors related to textiles. We hardly notice the relationship because so few of us know how our cloth is made. Even so our vocabulary to describe our most advanced technology and discoveries use these terms.

Textiles

as Art

as the Feminine

as Our Language

Discovering Women Obscured, Distorted, and Omitted

Throughout recorded history, and probably in ages before, textiles have been a means of empowering and constraining women, often at the same time. In the graves of the historical Amazons, we find both weapons for fighting and whorls for spinning. In Geoffrey Chaucer's Canterbury Tales, we find both the wealthy and wiley Wife of Bath and nearly wordless Emelye, object of love in the Knight's Tale.

Textiles as High Art

In the history of textile art, only in recent centuries has it been consistently relegated to "craft" rather than high art like painting and sculpture. As textile work was done increasingly in private spaces, as opposed to public spaces like painters and sculptures, it was proportionately devalued as feminine work. But this work, such as Opus Anglicanus, done mostly by women was highly priced art sought after by royalty and popes. Unfortunately, textile art does not endure over time like painting, sculpture, and architecture, mediums mostly available to men.

From: Uppsala Cathedral Parish, Uppland

Dated: late Middle Ages / 1450-1460-tal

Manufactured in: Sweden and Northern Europe

Material: Wire, silk, silk, pearls, plain weave

Opus Anglicanus

Gold and silk, 14th century

Textiles in History and Myth

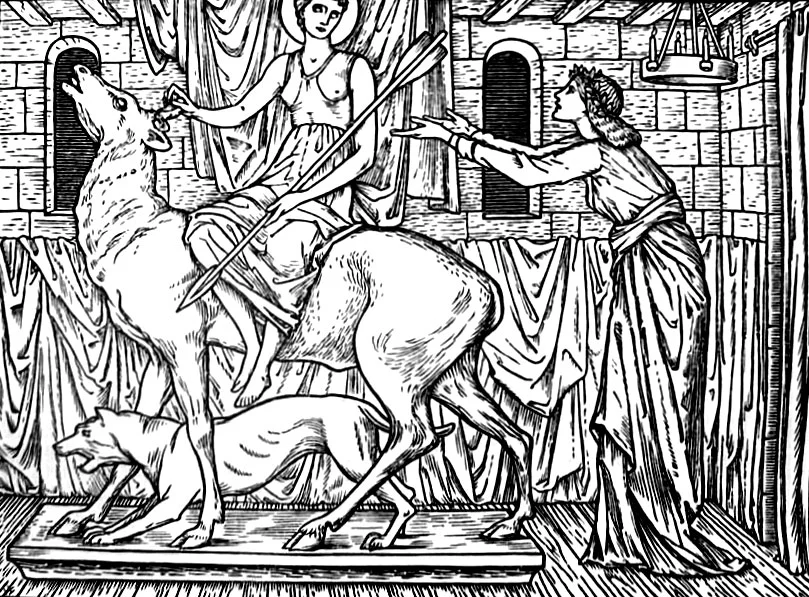

In the ancient world textile work was so highly regarded that even the goddesses performed it. The Tudor Queen Elizabeth was an accomplished embroiderer and wore elaborate embroidery work on her garments such as the very symbolic snake seen below embroidered on her sleeve. Some Viking weaver women were believed to be able to weave the future. In the American Southwest, Spider Grandmother is the creator of the world. Athena (Minerva) is a divine weaver, jealous of her art. Perhaps the most feared were the three Fates envisioned as spinners. Human fate was represented as a thread spun by Clotho. Lachesis unspooled it from the spindle, and Atropos decided when the person died and snipped the thread at that length. The Roman name them Nona,Decuma, and the ominously named Morta.

Our Language as Textiles

In describing our most sophisticated technologies and discoveries we often use terms from textile production to describe them.

The words “text” and “textile” demonstrate the importance of spinning thread, weaving cloth, and adorning cloth with words and literature. The Latin word “text” means “woven.” Weaving, spinning, and embroidering are the source for fundamental analogies to how we understand the way that words form patterns to make a sentence or the way we can understand or enjoy a story.

We use terms such as “texting” as we “spin our yarns” on digital phones or project our “texts” on Smartboards. Or, perhaps we may “get our hackles up” when our computers will not properly “spool” information on our printers, or when we read a “thread” on Facebook without realizing that we are using terms from cloth production. I am submitting the “warp and weft” of my thoughts on textiles via the World Wide “Web.” As part of the “fabric of our lives,” we Alabamians appreciate a little “homespun” humor that perhaps “embroiders” the truth a bit whether we are “dyed in the wool” Alabama or Auburn fans. We pride ourselves in our “tight-knit” families who support us when things begin to “unravel” and our lives are in a “tangle.” Even our NASA scientists in Huntsville incorporated “String Theory” in projecting the path of the Space “Shuttle” as they “canvas” the universe for the best trajectory. Of course, none of us ever want to feel like we have been “fleeced” by a “chintzy” or “shoddy” product. Thus, the “common thread” in this paragraph is that terms for textile production that we use in everyday speech communicate fundamental ways in which we make sense of our lives.

Textiles are “interwoven” in our speech in the ways that we understand and interpret the very “fiber” of our being.